AI Layoffs: The Double-Edged Sword of Robotic Revolution – More Time for Hobbies or a Fast Track to Mental Illness?

- ryanshortpmhnp

- Aug 18

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 18

Picture this: It’s Monday morning. Instead of hitting snooze, wrestling traffic, and bracing yourself for another meeting about “leveraging synergies,” you’re… free. Completely, utterly free. Some clever AI just automated your job out of existence. Finally, you can pursue your passion for writing the great American novel, juggling flaming chainsaws, or mastering the art of mid-afternoon napping.

Sounds like utopia, right?

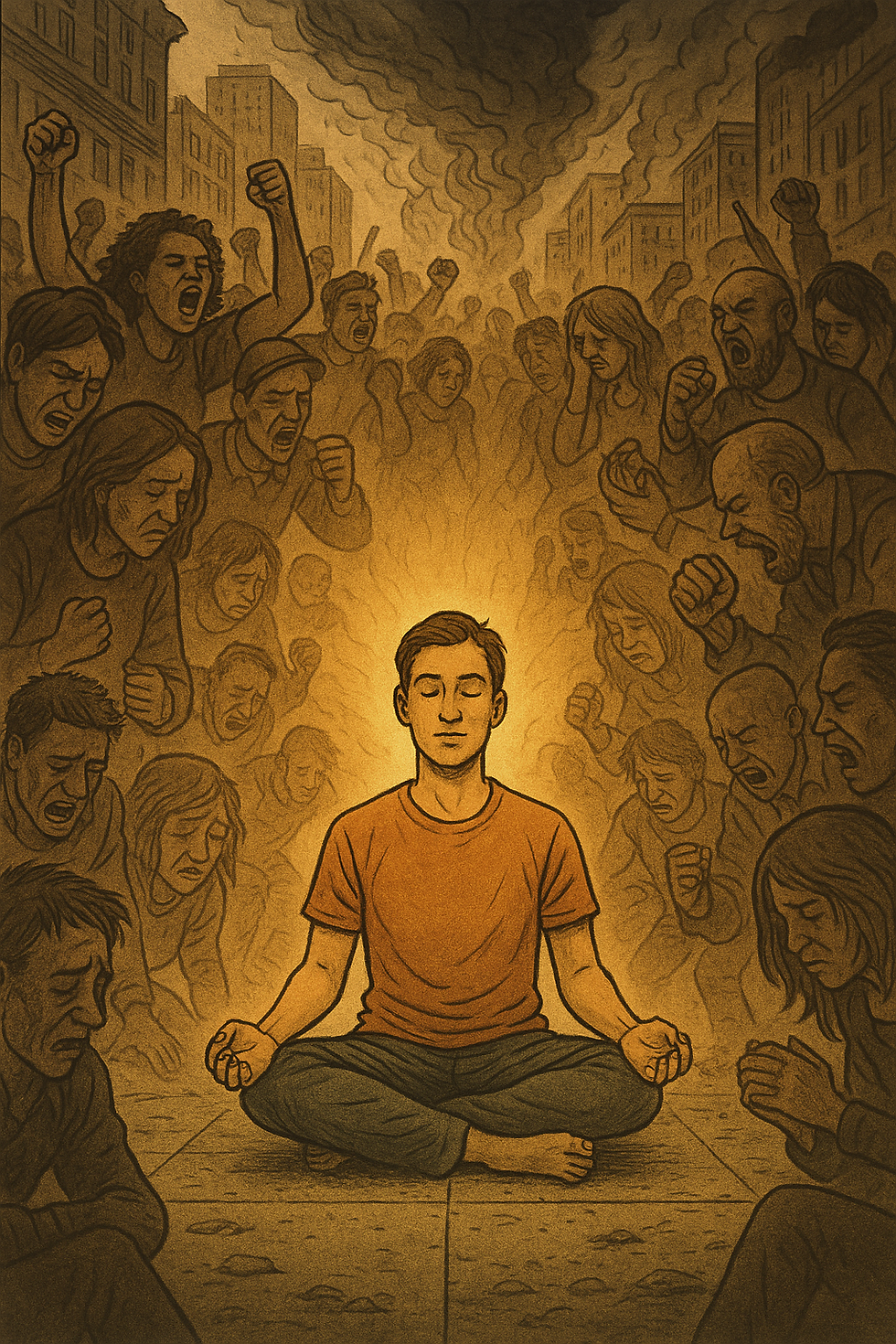

That’s the vision many AI optimists paint: automation as a net benefit. No more tedious work, just humans flourishing in creativity, relationships, and hobbies—bills covered by universal basic income (UBI). But here’s the problem: most of us aren’t built for unlimited free time. While a small minority might thrive, the majority risk falling into a stew of anxiety, depression, addiction, and loneliness. In short: no obligations, no purpose, no schedule… no bueno.

Let’s look at why—through a mix of humor, hard truths, and some solid science.

The Allure (and Trap) of Limitless Free Time

It’s not crazy to think AI could relieve us of boring jobs. Who hasn’t fantasized about quitting their 9-to-5 to become a professional beachcomber? Studies show that repetitive, unrewarding work does weigh on mental health. But there’s a catch: humans don’t do well with blank calendars.

Unemployment research makes this painfully clear. A large meta-analysis found unemployment reduced mental health by a medium effect size (d ≈ 0.5), with higher depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic complaints across the board (Paul & Moser, 2009). Another global review confirmed unemployment consistently raises the risk of depression, anxiety, and even suicide, especially when prolonged (Kim & von dem Knesebeck, 2016).

Translation? Your brain’s inner monologue shifts from “I’m a productive member of society” to “I’m a useless lump on the sofa.”

Addiction: When Free Time Becomes a Vice

Obligations aren’t just annoying—they also keep us accountable. Remove work, and many people lose a built-in system of self-control. Unsurprisingly, research shows unemployment correlates strongly with substance use. A recent review across North America and Europe found job loss increases alcohol, opioid, and drug misuse (Henkel, 2011).

Now imagine 20% of working Americans suddenly laid off due to AI. Millions with endless time and zero guardrails. That’s not freedom—that’s a national invitation to day-drink before noon. UBI might buy the groceries, but it won’t restore the dopamine that deadlines, teamwork, and paychecks once provided.

The Loneliness Problem

We often fantasize about never having to deal with coworkers again. No more passive-aggressive emails, no more “reply all” disasters. But here’s the twist: work is one of the main places we get consistent social contact. Strip that away, and isolation creeps in.

Loneliness isn’t just uncomfortable; it’s lethal. Some studies suggest chronic loneliness has health effects comparable to smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Holt-Lunstad, 2015). During the pandemic, when millions lost work and daily routines, people with reduced social interaction had up to 3.7 times higher odds of severe psychological distress (Butterworth et al., 2021).

So yes, you may escape office small talk. But instead, it’s just you, your cat, and the echo chamber of your own thoughts. Even introverts eventually need some human banter to stay sane.

Purpose: The Secret Ingredient

At its core, the problem isn’t just losing income. It’s losing purpose. Work gives us structure, identity, goals—even when it’s not glamorous. Psychologists Creed & Macintyre argue that employment fulfills basic needs: time structure, social contact, status, and activity (Creed & Macintyre, 2001). Without it, people drift.

One prospective study of 300 men found that unemployed individuals reported more anxiety, depression, and physical complaints, while those with strong family support fared better (Feather & Barber, 1983). Globally, a 2024 analysis across 201 countries linked unemployment with increased rates of anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, drug use, and eating disorders (Liu et al., 2024).

It’s like being handed a blank canvas with no brushes. A few gifted self-starters might paint masterpieces. Most of us just stare at it, paralyzed.

Who Thrives—and Who Doesn’t

Yes, some will flourish. The self-motivated artist, inventor, or quantum-knitting podcaster may thrive when freed from obligations. But research suggests they’re outliers. For most, sudden joblessness leads to apathy, disengagement, and worsened mental health.

One review showed that returning to work significantly reduced depression and anxiety, even if the new job wasn’t “ideal” (Winkelmann, 2009). In other words, having somewhere to be is better than endless free time—even if that somewhere involves spreadsheets.

So…What Do We Do About It?

AI is not evil—it’s a tool. It may well cure diseases, solve climate problems, and finally fix traffic lights. But pretending that AI-driven layoffs will be a universal blessing is like building a rocket without a parachute.

If mass automation is inevitable, we need mental-health safety nets as sturdy as UBI. That means:

Retraining & re-employment programs that focus not only on skills but also on community and purpose.

Accessible mental health services, including CBT, shown to reduce depression in the unemployed (McKee-Ryan et al., 2023).

Structured volunteer or civic opportunities to replace the lost social scaffolding of work.

Gradual AI integration instead of mass, overnight layoffs.

Otherwise, the utopia of “no more jobs” could quickly spiral into a mental-health avalanche.

Conclusion: A Cautionary Cheer

So yes—AI might free us from drudgery. But unless we build systems of purpose, community, and support, freedom can feel a lot like falling.

For a lucky few, automation will spark new passions and creative renaissances. For the rest? We risk trading commutes and cubicles for isolation, addiction, and existential dread.

In other words: the robots won’t destroy us. But without careful planning, the absence of Monday morning meetings just might.

References

Paul, K.I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior.

Kim, T.J., & von dem Knesebeck, O. (2016). Perceived job insecurity, unemployment and depressive symptoms: A systematic review. Journal of Economic Surveys.

Butterworth, P., et al. (2021). Work loss during COVID-19 and mental health. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Henkel, D. (2011). Unemployment and substance use. Current Drug Abuse Reviews.

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality. Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Feather, N.T., & Barber, G. (1983). Unemployment and depression: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Liu, Y. et al. (2024). The impact of unemployment on mental health globally. Frontiers in Public Health.

Winkelmann, L. (2009). Unemployment, social capital, and well-being. Health Affairs.

McKee-Ryan, F., et al. (2023). Interventions for unemployed people: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology.

Creed, P.A., & Macintyre, S.R. (2001). The relative effects of deprivation of employment and quality of employment on mental health. Social Science & Medicine.

Comments